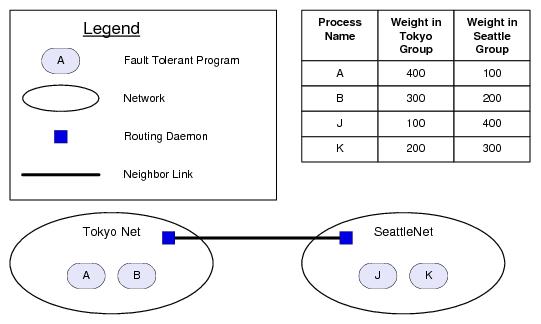

Figure 20 illustrates a situation with two levels of fault tolerance. Network sites in Tokyo and Seattle are connected by a WAN link, and Rendezvous routing daemons forward messages on demand between the two sites.

The active Tokyo process listens for requests that carry the subject name TOKYO.REQUEST. The active Seattle process listens for requests that carry the subject name

SEATTLE.REQUEST.

To administer fault tolerance at the Tokyo site, processes A and B join a fault tolerant group named TOKYO.APP1. A has higher weight than B, so A is initially active. The group’s active goal is one, so only one member of the group actively processes requests. Similarly, processes J and K in Seattle join a group named

SEATTLE.APP1. J has higher weight than K, so J is initially active.

For long-distance fault tolerance coverage, Seattle processes J and K join the Tokyo fault tolerant group, TOKYO.APP1; and Tokyo processes A and B join the Seattle fault tolerant group,

SEATTLE.APP1. The table in

Figure 20 lists the relative weights of all four processes in each of the two fault tolerance groups. Notice that within each group, local members have higher weight than distant members, so a distant member activates only when both local members fail or withdraw from the group.

If both Tokyo processes A and B fail, Seattle process K takes their place. When K receives a prepare-to-activate hint, it begins listening to the subject TOKYO.REQUEST. When the Rendezvous routing daemon detects the new listening interest, it begins forwarding the messages with subject

TOKYO.REQUEST from Tokyo to Seattle, where K receives them. When Rendezvous fault tolerance software instructs K to activate, K begins processing those request messages, sending the results back to clients in Tokyo.

For long-distance fault tolerance coverage, Seattle processes J and K join the Tokyo fault tolerant group, TOKYO.APP1; and Tokyo processes A and B join the Seattle fault tolerant group, SEATTLE.APP1. The table in Figure 20 lists the relative weights of all four processes in each of the two fault tolerance groups. Notice that within each group, local members have higher weight than distant members, so a distant member activates only when both local members fail or withdraw from the group.If both Tokyo processes A and B fail, Seattle process K takes their place. When K receives a prepare-to-activate hint, it begins listening to the subject TOKYO.REQUEST. When the Rendezvous routing daemon detects the new listening interest, it begins forwarding the messages with subject TOKYO.REQUEST from Tokyo to Seattle, where K receives them. When Rendezvous fault tolerance software instructs K to activate, K begins processing those request messages, sending the results back to clients in Tokyo.

For long-distance fault tolerance coverage, Seattle processes J and K join the Tokyo fault tolerant group, TOKYO.APP1; and Tokyo processes A and B join the Seattle fault tolerant group, SEATTLE.APP1. The table in Figure 20 lists the relative weights of all four processes in each of the two fault tolerance groups. Notice that within each group, local members have higher weight than distant members, so a distant member activates only when both local members fail or withdraw from the group.If both Tokyo processes A and B fail, Seattle process K takes their place. When K receives a prepare-to-activate hint, it begins listening to the subject TOKYO.REQUEST. When the Rendezvous routing daemon detects the new listening interest, it begins forwarding the messages with subject TOKYO.REQUEST from Tokyo to Seattle, where K receives them. When Rendezvous fault tolerance software instructs K to activate, K begins processing those request messages, sending the results back to clients in Tokyo.